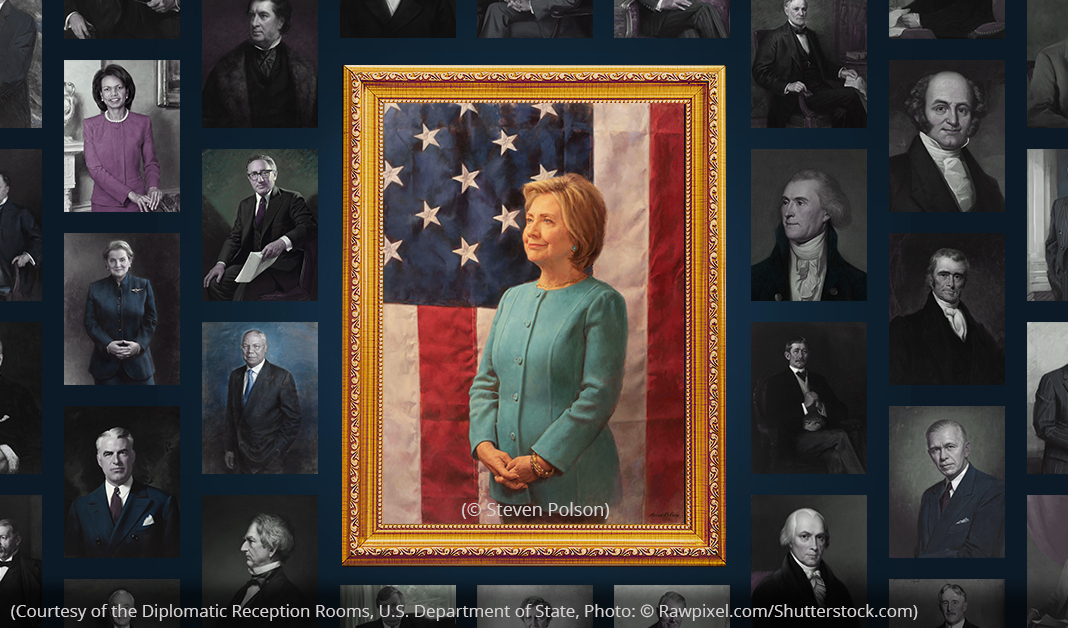

The Department of State unveiled a portrait of its 67th secretary, Hillary Rodham Clinton, this week, adding it to a historically and artistically significant gallery that includes paintings of Thomas Jefferson, the first U.S. secretary of state, and his many successors in the role.

The full collection of preserved diplomatic history dates from the time of America’s founding and includes rare porcelain, antique furniture and oil paintings from the 18th century to the present day. Virginia Hart, director of the Diplomatic Reception Rooms where the collection is housed, says the portraits of secretaries of state tell the story of the nation’s artistic development.

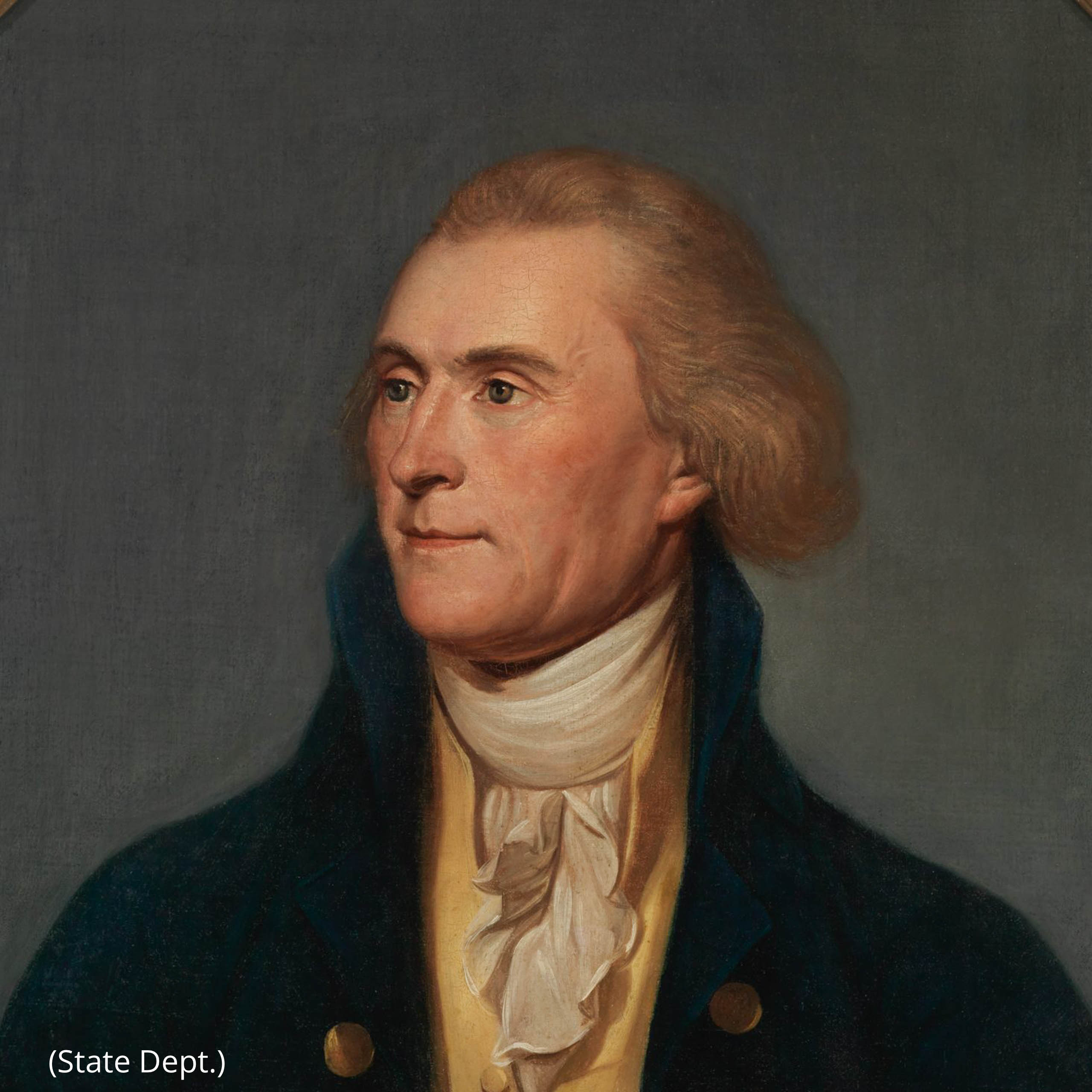

Among the early portraits, Jefferson’s is among the most striking. Having served as secretary from 1790–1793, before becoming the third U.S. president in 1801, Jefferson sat for several artists. The State Department’s 1791 portrait, attributed to artist Charles Willson Peale, arguably captures the first secretary at his most dynamic.

He is posed against a plain backdrop. (Increasingly, American artists stripped background details from portraits in order to highlight the leaders themselves and to imply their democratic values by eliminating ornate furnishings.)

Jefferson, in his 40s, appears youthful and alert, his head turned in a three-quarters view as he looks into the distance. The portrait creates the impression of a statesman leading a young nation as it forges an experiment in self-governance.

Jasmine Sewell, an expert on portraiture whose New York-based company, Sewell Fine Portraiture, represents contemporary portrait artists, notes that 18th- and 19th-century American artists, nevertheless, did go overseas to study the techniques of their European contemporaries, as museums and art academies were not yet well established in the New World.

These American artists took note of their European peers’ handling of color, tone and composition, with special attention to the works of Joshua Reynolds and Thomas Gainsborough, Sewell says.

While some artists of that era created portraits marred by stiffness, others found ways to create dignified portrayals that left room for originality. And, while Cabinet secretaries tend to evoke fairly conventional representations, some portraits in the State Department’s collection pushed boundaries.

Take George Peter Alexander Healy’s 1883 portrait of Elihu Benjamin Washburne (at left, above). Painted from life, it shows a seated Washburne leaning forward and locking eyes with the viewer. The pose suggests considerable force of character. Another example is John Singer Sargent’s 1897 portrait of Thomas F. Bayard (at center, above). Loose brushstrokes outline the lightly modeled figure, lending it a modern touch and focusing attention on Bayard’s face, which is partly in shadow.

More recently, the 1950 portrait of Dean Acheson (at right, above) by Gardner Cox departed from convention, with its almost abstract backdrop. Its restraint marks it as a more contemporary work of the midcentury era.

21st-century portraits

Clinton’s portrait — painted by Steven Polson, who also painted former secretaries Madeleine Albright, Colin Powell and Condoleezza Rice — shows her smiling and standing sideways in front of an unfurled U.S. flag. Her hands are clasped as she looks off to her right.

Polson prepares for any portrait by researching his subjects and examining photos of them before meeting them. At the first meeting, he takes his own photos for preliminary sketches. Later, he submits two sketches to a subject for his or her consideration before the real work begins. While some are initially nervous to pose, or sit, for a portrait, most enjoy the process once it’s underway.

He enjoys getting to know his subjects. He found Clinton to be relaxed and witty. She asked about Polson’s new baby and talked about being a grandmother. (Albright brought doughnuts and coffee to the studio. Powell talked of his hobby of fixing old cars. Rice, who welcomed him into her home for a photo shoot, was gracious and pleasant.)

Polson says that an artist has to keep trying until he gets it right. If a sitter’s spouse or children react with joy to a portrait, he knows he’s got it. “With portraiture, you’re trying to do something that people will enjoy and look at,” he says. “And there has to be some graphic strength, so it won’t fade into the wall.” (In artistic terms, “graphic strength” refers to a clear, vivid picture that draws the viewer’s attention.)

Painting Cabinet members is like painting other portraits, except in one regard, Polson says: “What’s behind a Cabinet member’s official portrait is love and admiration for the service a person has given to their country and how they’re loved by the people who worked with them.”