Our series Inside XR Design highlights and unpacks examples of great XR design. Today we’re looking at Beat Saber (2019) and why its most essential design element can be used to make great VR games that have nothing to do with music or rhythm.

You can find the complete video below, or continue reading for an adapted text version.

More Than Music

Welcome back to another episode of Inside XR Design. Now listen, I’m going to say something that doesn’t seem to make any sense at all. But by the end of this article, I guarantee you’ll understand exactly what I’m talking about.

Beat Saber… is not a rhythm game.

Now just wait a second before you call me insane.

Beat Saber has music, and it has rhythm, yes. But the defining characteristic of a rhythm game is not just music, but also a scoring system that’s based on timing. The better your timing, the higher your score.

Now here’s the part most people don’t actually realize. Beat Saber doesn’t have any timing component to its scoring system.

That’s right. You could reach forward and chop a block right as it comes into range. Or you could hit it at the last second before it goes completely behind you, and in both cases you could earn the same number of points.

So if Beat Saber scoring isn’t about timing, then how does it work? The scoring system is actually based on motion. In fact, it’s actually designed to make you move in specific ways if you want the highest score.

The key scoring factors are how broad your swing is and how even your cut is through the center of the block. So Beat Saber throws these cubes at you and challenges you to swing broadly and precisely.

And while Beat Saber has music that certain helps you know when to move, more than a rhythm game… it’s a motion game.

Specifically, Beat Saber is built around a VR design concept that I like to call ‘Instructed Motion’, which is when a game asks you to move your body in specific ways.

And I’m going to make the case that Instructed Motion is a design concept that can be completely separated from games with music. That is to say: the thing that makes Beat Saber so fun can be used to design great VR games that have nothing to do with music or rhythm.

Instructed Motion

Ok so to understand how you can use Instructed Motion in a game that’s not music-based let’s take a look at Until You Fall (2020) from developer Schell Games. This is not remotely a rhythm game—although it has an awesome soundtrack—but it uses the same Instruction Motion concept that makes Beat Saber so much fun.

While many VR combat games use physics-based systems that allow players to approach combat with arbitrary motions, Until You Fall is built from the ground up with a notion of how it wants players to move.

And before you say that physics-based VR combat is objectively the better choice in all cases, I want you to consider what Beat Saber would be like if players could cut blocks in any direction they wanted at all times.

Sure, you would still be cutting blocks to music, and yet, it would be significantly harder to find the fun and flow that makes the game feel so great. Beat Saber uses intentional patterns that cause players to move in ways that are fluid and enjoyable. Without the arrows, player movements would be chaotic and they’d be flailing randomly.

So just like Beat Saber benefits by guiding a player to make motions that are particularly satisfying, combat in VR can benefit too. In the case of Until You Fall, the game uses Instructed Motion not only to make players move a certain way, but also to make them feel a certain way.

When it comes to blocking, players feel vulnerable because they are forced into a defensive position. Unlike a physics-based combat game where you can always decide when to hit back, enemies in Until You Fall have specific attack phases, and the player must block while it happens, otherwise you risk taking a hit and losing one of just three hit points.

Thanks to this approach, the game can adjust the intensity the player feels by varying the number, position, and speed of blocks that must be made. Weak enemies might hit slowly and without much variation in their attacks. While strong enemies will send a flurry of attacks that make the player really feel like they’re under pressure.

This gives the developer very precise control over the intensity, challenge, and feeling of each encounter. And it’s that control that makes Instructed Motion such a useful tool.

Dodging is similar to blocking, but instead of raising your weapon to the indicated position, you need to move your whole body out of the way. And this feels completely different from just blocking.

While some VR combat games would let the player ‘dodge’ just by moving their thumbstick to slide out of the way, Until You Fall uses Instructed Motion to make the act of dodging much more physically engaging.

And when it comes to attacking, players can squeeze in hits wherever they can until an enemy’s shield is broken, which then opens an opportunity to deal a bunch of damage.

And while another VR game might have just left this opening for players to hit the enemy as many times as they can, Until You Fall uses Instruced Motion to ask players to swing in specific ways.

Swinging in wide arcs and along particular angles deals the most damage and makes you move in a way that feels really powerful and confident. It’s like the opposite feeling of when you’re under attack. It really feels great when you land all the combo hits.

Continue on Page 2: Motion = Emotion

,

Motion = Emotion

So what can we learn from Instructed Motion when it comes to XR design?

Well, it’s clear that certain motions can be fun, but beyond fun, certain motions can make players feel a certain way—like being able to add flavor to their experience.

Take for example the beat map in the track Radioactive. The motions in this song are these huge punchy hits that really speak to the song’s powerful lyrics. And there’s one part where you fling your hands way up in the air right as there’s a break in the music and the singer takes a deep breath—a motion that makes you feel perfectly in tune with that moment in the song.

On the other hand, the beat map of Harder, Better, Faster, Stronger literally makes you move with robotic motions, which perfectly aligns with both the tone and theme of the song.

Intentionally making players move in these unique ways makes these beat maps feel completely unique from one another by making the player experience different feelings while they play.

This connection between specific motions and how they make players feel means you can even think of Instructed Motion as Instructed Emotion.

But how can you apply this to games that don’t have anything to do with music?

Rather than starting by building out a world and filling it with objects and enemies and then figuring out exactly how players will interact with those things, my recommendation is—before you do anything else—sit down and come up with an idea of how you want your players to feel—like a specific set of emotions you want them to experience.

Once you have that feeling locked down, you can experiment with motions and interactions that encourage that emotion.

This is exactly how Schell Games approached the development of Until You Fall.

Until You Fall Producer Kirsten Rispin told me the studio built the game around the idea of making players feel like a “sword god.” Specifically, she said the team honed in on the words “powerful, strong, and smart” for how they wanted players to feel while they played.

But how do you build a combat system that creates those feelings? Instructed Motion was the key.

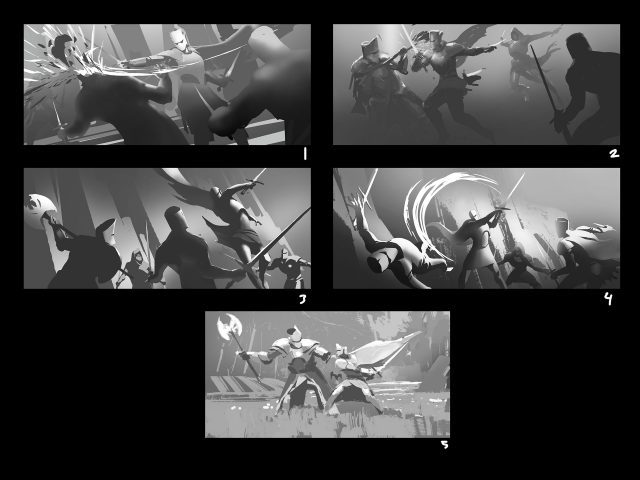

Until You Fall Art Director Justin DeVore told me the team worked hard to “choreograph the combat to feel powerful and complex.”

“We tried to design poses that would pop onto the screen in ways that felt good. If we put a block angle in one direction, we want to make sure the next angle will make it feel cool to have moved to that new position. And so there was a lot of iteration and back and forth on making sure the choreography of the Instructed Motion mechanics delivered the ‘Sword God’ feeling we were chasing.”

While many of the game’s Instructed Motion mechanics use explicit visual indicators, some of the mechanics that make players feel powerful are more subtle. For example, the way you pick your reward at the end of each stage by crushing it in your hand.

It would have been much easier to use a laser pointer to select the reward from a menu screen, but this simple motion absolutely contributes to the feeling of being powerful within the game.

So, as the final takeaway: making the most of Instructed Motion means matching the motions—and thus the emotions—to the fantasy you want to deliver.

If you’re making a horror game, the player should feel scared. If you’re making a stealth game, the player should feel skilled and sneaky. And if you’re making an action game, the player should feel capable and deadly. So spend time thinking about what motions can contribute to the particular feelings that your game wants to deliver to players.

– – — – –

If you want to see how Until You Fall delivers the feeling of being a Sword God, you can find it on Quest, PC VR, PSVR, and PSVR 2.

Enjoyed this breakdown? Check out the rest of our Inside XR Design series and our Insights & Artwork series.

And if you’re still reading, how about dropping a comment to let us know which game or app you think we should cover next?